For decades, women in Indian films and shows have existed in extremes. Either the pious maa, forever sacrificing, or the hypersexualised maal, placed on screen to titillate, and we lapped it up. Cheered for the brooding hero, swooned at the bromance, cried at the mother’s death, and danced to the item number. But we never stopped to ask, where is she in all this? Who is she, beyond how she serves the man?

The pattern is so normalised we barely notice it anymore, a female character can rarely transcend the binary of ‘maa’ (mother) or ‘maal’ (objectified woman). This isn't just bad writing, it's systematic erasure. Let's revisit some beloved classics through this critical lens and see if they hold up.

Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara – Finding Yourself… Through Women

Three men, three life lessons, three countries. But what about the women? They're merely pit stops on the male protagonists' roads to self-realisation.

Laila functions as both scuba instructor and life coach, Natasha embodies the stereotypical controlling fiancée trope, and Ariadna is reduced to a romantic encounter at the end of a flamenco sequence. This acclaimed film showcases male liberation, achieved through interactions with women, but never for them.

The message becomes clear: finding yourself is an exclusively male journey. Women exist only to facilitate men's personal growth.

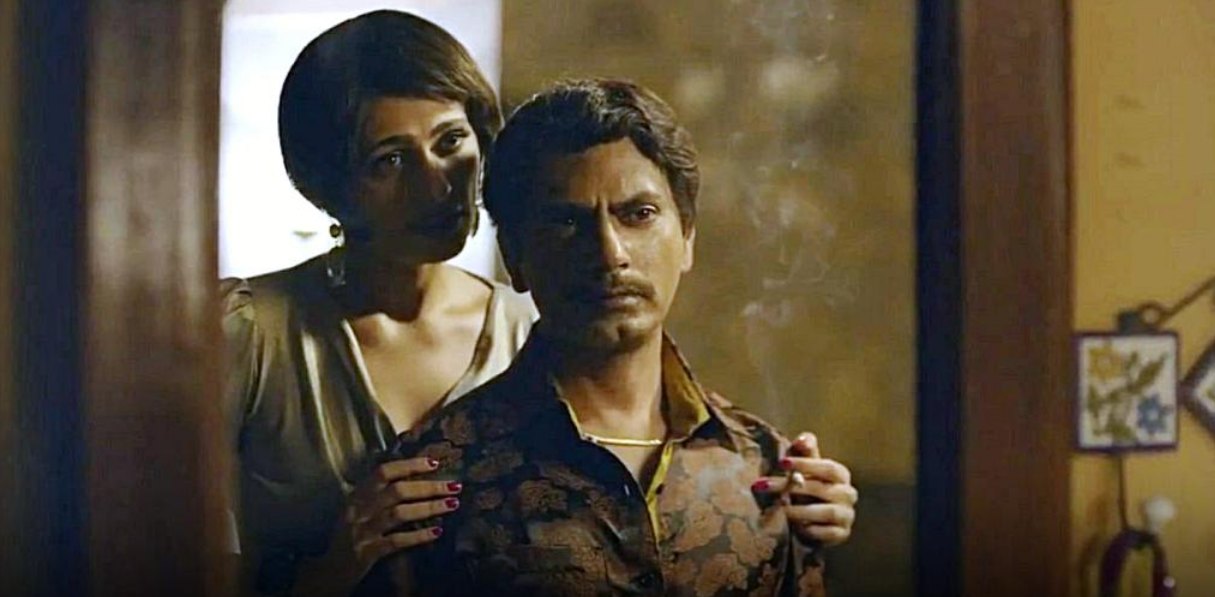

Sacred Games – Women as Collateral Damage

Gritty, layered, unforgettable. And yet, Sacred Games kills off every woman who dares to be powerful.

Kukoo, a bold transgender character, was shot dead. Anjali, an intelligence officer, has gone in a flash. Jojo, a morally complex agent, was executed. These weren’t just casualties. These women were eliminated due to male trauma. Their deaths propelled the male leads forward, adding gravitas to their stories. But who mourned them? Who told their stories?

This wasn’t a plot necessity. It was erasure.

Don't Miss:Khauf Isn’t Just Horror—It Reflects Everyday Fears Women Live With

Gangs of Wasseypur – Seven Wives, Zero Agency

Two generations of gangsters. Five hours of cinema. Countless shootouts. And not a single woman with narrative control.

Nagma spews abuse but remains a background figure. Mohsina is all lipstick and longing looks. Durga seduces silently, given barely a line of her own. The film is brilliant, but when it comes to female agency, it's a black hole. Even with many women on screen, the story remains stubbornly male.

Money Heist – Breaking Hearts, Not Systems

They held guns, led coups, and outwitted the cops, and yet, the women of ‘Money Heist’ were written with one fate: to fall apart.

Tokyo, Nairobi, and Raquel all start strong, all end entangled in some emotional chaos. Their arcs aren't about growth or leadership; they're about heartbreak. A revolution written by men still chooses a man as a mastermind. Even in rebellion, women are denied full power.

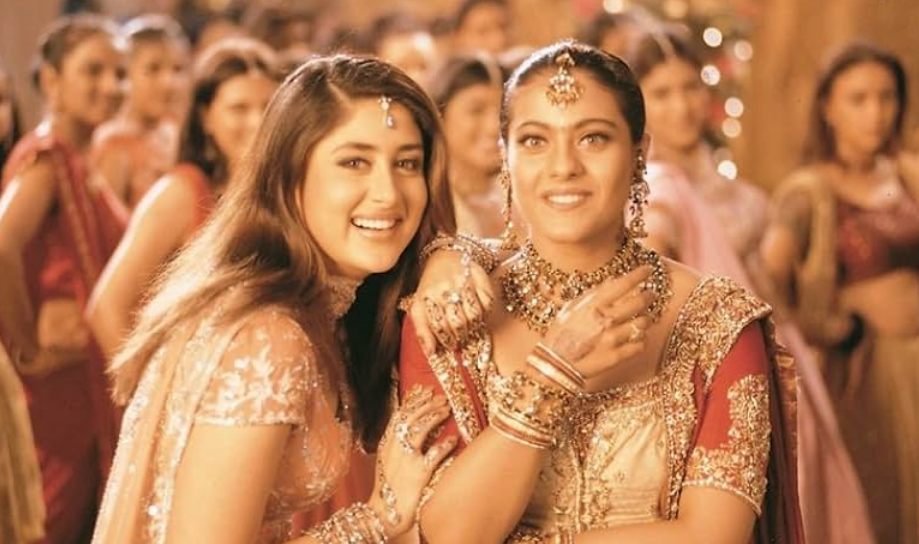

Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham – Patriarchy in Designer Couture

Despite strong female performances, emotional intensity, and unforgettable styling from a mother's intuition to Anjali's unapologetic middle-class pride to Poo's refreshing self-confidence these characters have virtually no consequence to the storyline.

Whatever female background gets established (like the Chandni Chowk connection) becomes a narrative liability to be forgotten. The women dance, wear bangles, and look beautiful, but have no agency, only the men make meaningful decisions. It's patriarchy dressed in designer Manish Malhotra outfits.

Don't Miss:Moms Without Melodrama: 11 Times Bollywood Got It Just Right

Beyond Criticism: Why This Matters

When films consistently erase or diminish women, it isn't a mistake, it's a blueprint. When writers create female characters with no arc, no dreams, no flaws, and no fire, they communicate a clear message: women don't matter unless they matter to a man.

This isn't about cancelling cult classics, it's about recognising cultural conditioning. Because when women lack names, choices, or even friendships on screen, regardless of a film's other merits, an entire perspective is missing.

We need to rewatch our favourites with eyes wide open, recognising that if a female character merely decorates the scene, she's not a character at all, she's a costume. Cinema can and must do better to represent the full human experience, not just half of it.

For more such stories, stay tuned to HerZindagi.

Image Courtesy: IMDb

Take charge of your wellness journey—download the HerZindagi app for daily updates on fitness, beauty, and a healthy lifestyle!

Comments

All Comments (0)

Join the conversation